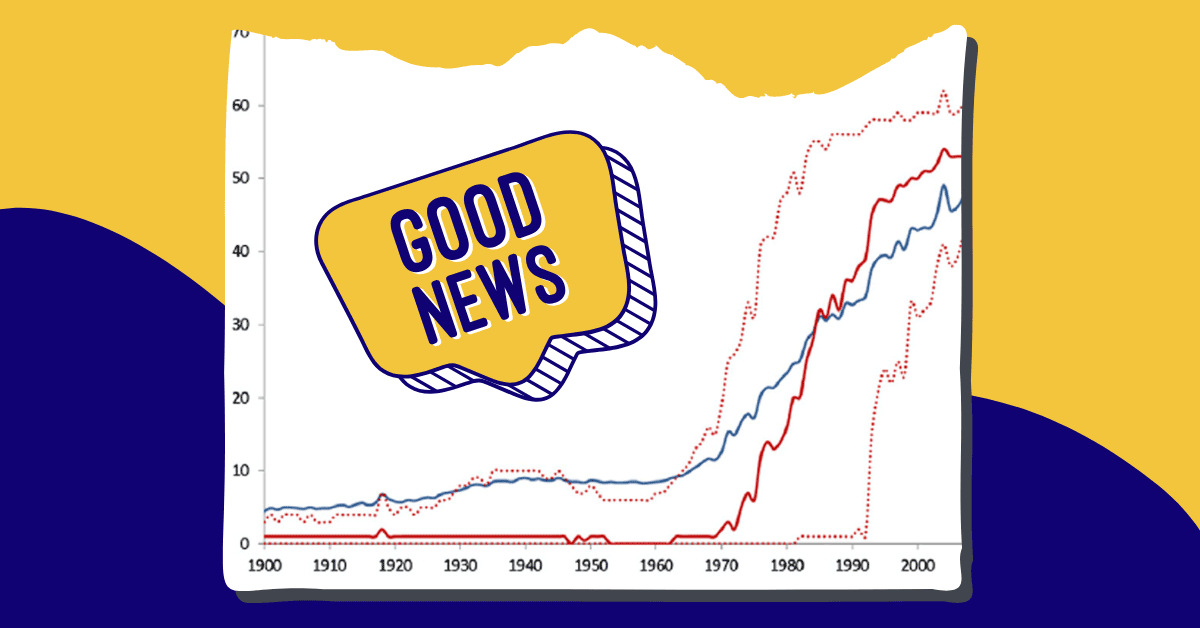

The lifespan of people with Down syndrome is higher than ever before, according to the Global Down Syndrome Foundation.

In fact, the average lifespan of folks with Down syndrome has increased from 25 years in 1983 to about 60 years today.

Down syndrome is a genetic disorder in which an individual has three copies of chromosome 21, instead of two. From birth, people with Down syndrome experience physical and intellectual delays, but there is a wide range of abilities within the population (which accounts for about one in every 700 babies born in the U.S. every year).

Research also connects Down syndrome genetic predispositions to other medical conditions, including congenital heart defects, sleep apnea, Alzheimer’s disease, celiac disease, autism, childhood leukemia, and seizures.

While these conditions certainly impact the length and quality of one’s life, it’s important to note that the lower life expectancy of people with Down syndrome is linked to the historical inhumane practice of institutionalization.

Prior to the 1980s, the vast majority of people with Down syndrome in the U.S. were placed in institutions and experienced neglect, abuse, and lacked access to vital resources and medical care.

With the end of this inhumane treatment, the life expectancy of these folks skyrocketed.

That being said, the health care system is not necessarily equipped to handle an influx of adult patients with Down syndrome.

In fact, the Global Down Syndrome Foundation lists only 15 medical programs in the country that serve Down syndrome patients who are 30 or older, which is especially troubling as adults encounter new symptoms or chronic health conditions in middle age.

“Taking care of kids is a whole different ball game from taking care of adults,” Moya Peterson, a nurse practitioner at the University of Kansas’s program, told KFF Health News.

Expanding care for adults with Down syndrome

While it’s important that systemic barriers to care are addressed on a nationwide level, it’s also heartening to know that more and more programs are emerging to address the questions that come with extra years.

Most urgently, researchers are studying the evolving needs of lifelong care as folks with Down syndrome may experience early-onset dementia and Alzheimer’s-like symptoms at extremely high rates.

“We hear from parents that this is the thing they worry about the most,” said Snehal Khatri, associate professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the medical director of UAB Sparks Pediatrics.

Khatri and her colleague Betsy Hopson are creating a new clinic to focus on care for those who have Down syndrome across their lifespans.

“We are adopting a lifespan model, to be able to say to patients and parents, ‘this is where we know that you are going; this is the trajectory,’” Hopson said in a press release. “We are excited to build the entire lifespan program, but addressing the palliative and memory challenges will really make us unique to anywhere in the country.”

The clinic came into being when Khatri, who is a member of the board of directors of Down Syndrome of Alabama, spoke with community members to see what was needed most. Many of them shared that what they were missing was help with the transition between pediatric and adult care.

“It is a very different experience in the pediatric world and the adult world,” Khatri said. “Insurance changes. What is covered changes. So being thoughtful in planning for these changes early is extremely important.”

Medical outcomes often decline for patients with Down syndrome during this transition into adulthood, Hopson said, as they work to find new doctors, gain independence, and potentially encounter new symptoms.

Hopson had prior experience in these transitions, as the university’s director of the Staging Transition for Every Patient Program, or STEP. This will provide an important framework for the new clinic, bringing in partnerships with existing medical providers.

“For the vast majority of patients, we will work with their existing clinicians,” Hopson said. “It is co-management.”

Not only will this work benefit the patients, but it will hopefully provide a greater framework for the medical field at large.

“You would be surprised at the number of primary care doctors who don’t know [adults with Down syndrome] exist,” Khatri said. “Having a dedicated clinic will improve adherence to medical guidelines for the pediatric patients.”

Texas A&M University also recently received a $1.8 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to research bone health in people with Down syndrome.

The INCLUDE Project grant will help scientists understand whether bone regeneration can help people with Down syndrome recover from fractures.

Ultimately, these two projects have the potential to make major breakthroughs in maintaining and improving the health of people with Down syndrome, as they continue to live longer and more meaningful lives.

Above all, social changes in attitude must be made to increasingly include people with Down syndrome in their own care — in their own futures.

“I just want her to be taken care of and loved like I love her,” the mother of a young woman with Down syndrome told KFF Health News. “I want her to be taken care of like a person, and not a condition.”

Header image courtesy of J Pediatr. 2013 Oct; 163(4): 1163–1168.